In the Hidden Waters of Steung Treng

In the remote wetlands of the Steung Treng province, in northeastern Cambodia, the Tonle Srepok River, a tributary of the mighty Mekong that originates in the central mountains of Vietnam, meanders through riparian forests and rural villages. There, in its calmer and shadier tributaries, where the water is dyed black by the decomposition of leaves and branches and the environment acquires an almost magical aura, lives a gem of aquatic biodiversity: the Betta stiktos.

This species, strictly endemic to the region, finds refuge in ponds, ditches, and small watercourses where riparian vegetation maintains mild temperatures and an acidic pH, ideal conditions for this unique fighting fish. However, its ecosystem faces growing threats: deforestation, intensive agriculture, and hydroelectric projects alter the flow and quality of the water, putting both this habitat and its inhabitants at risk.

Betta stiktos (male). Photo: Minh Trí Kiệt ©

Betta stiktos (female). Photo: Minh Trí Kiệt ©

A Closer Look!

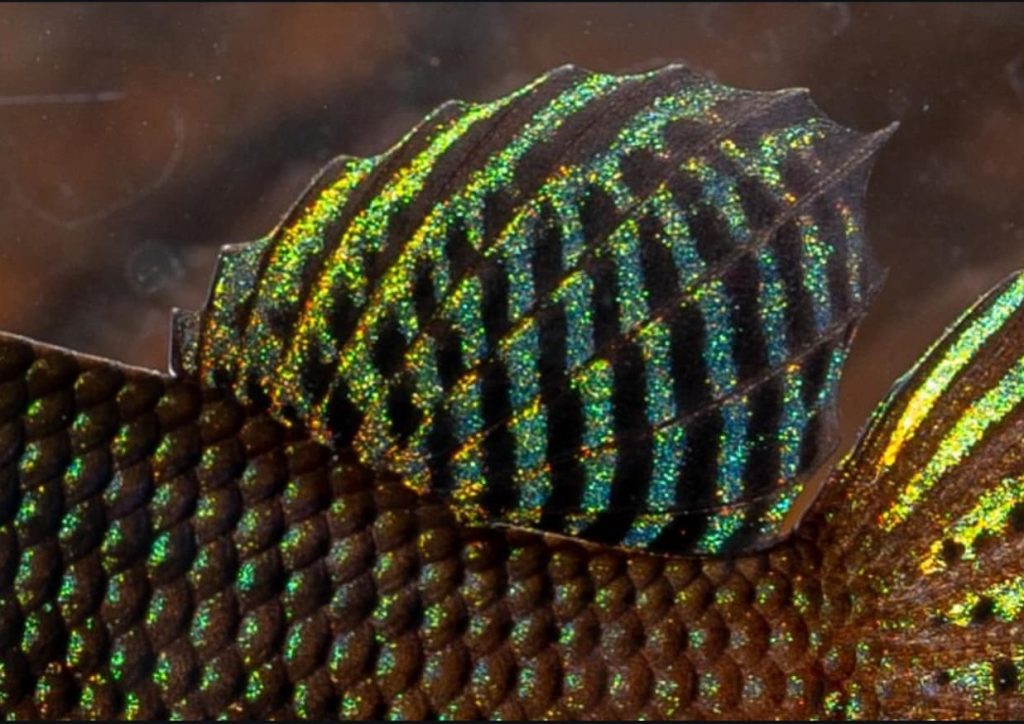

In Betta stiktos, the patterning on the operculum (the bony plate covering the gills) is just one of several key diagnostic characters that help identify the species. The operculum of Betta stiktos shows prominent metallic green–blue iridescence that is arranged in what can be described as a “snake-scale” pattern, appearing as rounded, scale-shaped patches rather than a uniform shine. It gives a mosaic-like shimmer across the cheek area, which in males is especially vivid, covering most of the operculum, and in females, is present but duller, sometimes only a partial green shimmer.

Betta stiktos (male). Photo: Minh Trí Kiệt ©

Comparatively, when looking at the patterning of the opercula of the most closely related species to Betta stiktos, in B. smaragdina, the operculum patterning tends to be more uniform and less broken up, like a smooth metallic patch. In B. mahachaiensis, it is densely iridescent and brighter, sometimes covering the whole cheek in solid green-blue. In wild B. splendens, the iridescence is weaker, often restricted to a small patch on the operculum or missing entirely, but Betta stiktos is unique for its fragmented, snake-scale appearance, displaying dark gaps between shimmering patches.

Betta smaragdina (opercular view). Photo: Gabor Horvath ©

Betta mahachaiensis. Photo: Gabor Horvath ©

Other Traits That Distinguish Betta stiktos

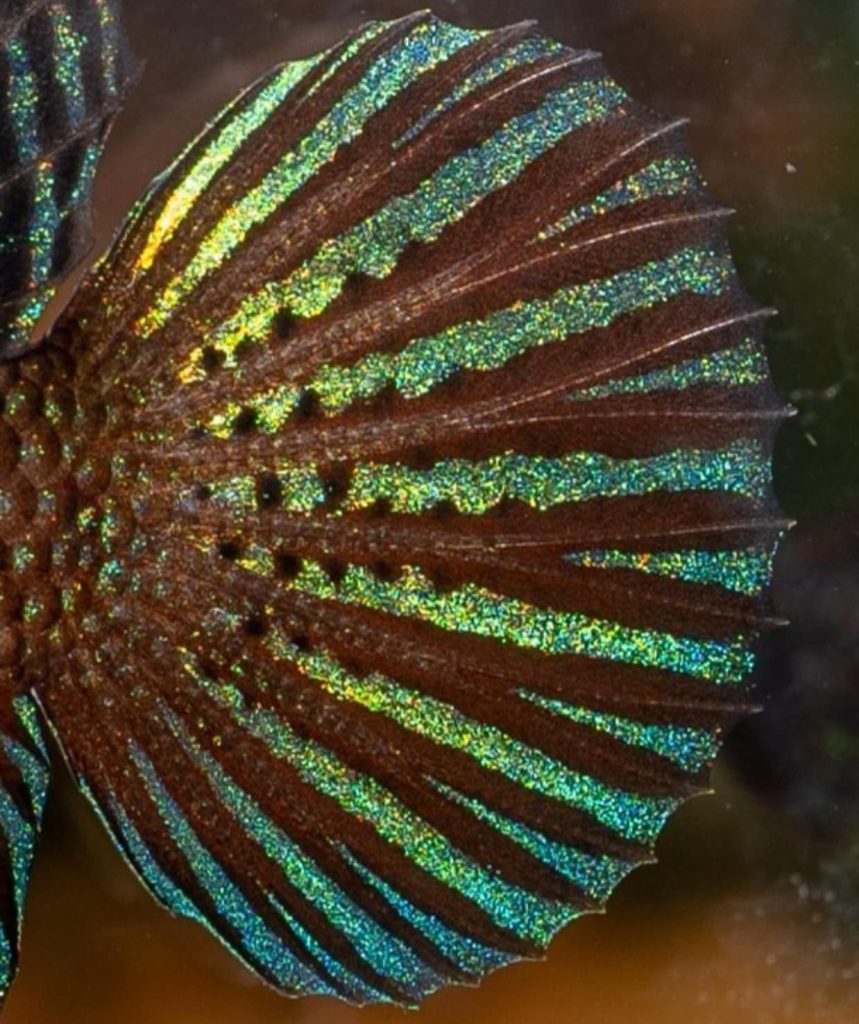

Size is a significant species indicator for Betta stiktos. Whereas B. smaragdina and B. mahachaensis tend to average out at around 4-5cm and B. splendens (wild) at around 5-6cm, B. stiktos has an average standard length of ~2.8cm! Dorsal fin markings also play a key diagnostic role in identifying Betta stiktos, having on average 7-9 strong transverse (vertical) black lines crossing the dorsal fin, whereas B. smaragdina has 5-7 weaker bars, B mahachaiensis has fewer, often obscured by iridescence, and B. splendens (wild) very rarely show this, more often displaying faint spots instead.

Betta stiktos (male dorsal fin). Photo: Minh Trí Kiệt ©

In the caudal fin, Betta stiktos displays up to 5 rows of small black spots; B. smaragdina, more typically, displays 3–4 rows. In B. mahachaiensis, these are much less distinct, lack clear spotting, but may have faint stripes, and in B. splendens (wild), it’s far more rare, but can present very faint spots.

Betta stiktos (male caudal fin). Photo: Minh Trí Kiệt ©

Morphological Diversity: Facial Patterns, B82, and Oleang Krous

Biologists and hobbyists have documented a fascinating variability arising in Betta stiktos, highlighting in particular, two variants in its iridescent head scale pattern that have been named ‘Type 1’ and ‘Type 2’. The main distinction between these two lies in the number and arrangement of the iridescent scales. Type 1 shows a smaller number of bright scales, arranged in a more aligned and defined manner, which creates a marked contrast between the green flashes and the dark background. Its fins, particularly the spade-shaped caudal fin, have a predominantly dark color with a distinct pattern that contributes to a solid appearance. In contrast, Type 2 is characterized by a greater number of iridescent scales, distributed in a more dispersed and extensive way, offering a broader and more intense luminous aspect. The fins in this variant are also prominent; the dorsal fin is broad and rounded, while the anal fin is wide and extends from the base to the tip with a pointed shape, creating an elegant silhouette that contrasts with its compact body.

Type 1 and Type 2 facial phenotypes. Photos: Cambodia Wild Betta Conservation ©

Within this variability, recent studies and field observations have made it possible to identify populations with distinctive morphological characteristics, such as the “B82” specimens and those from the Oleang Krous region in Steung Treng. These populations show notable differences in the coloration and patterning of their fins and in the extent of iridescence on the head. The fish from Oleang Krous, for example, tend to exhibit more vibrant blue and turquoise-green tones on their dorsal and caudal fins, as well as a wider dispersion of bright scales on the head, similar to Type 2. On the other hand, “B82” individuals may have darker fins and more subtle and defined iridescent patterns, suggesting a greater affinity with Type 1. These distinctions not only enrich our understanding of the intraspecific diversity of Betta stiktos but also underscore the importance of studying each population individually for its conservation. Together, these traits from the iridescent pattern of its scales to the specific shape of its fins and the variations between populations are not just scientific details; they tell the story of a fish that has evolved to thrive in the dark, tranquil waters of the Steung Treng wetlands, making it a true natural treasure of Cambodia.

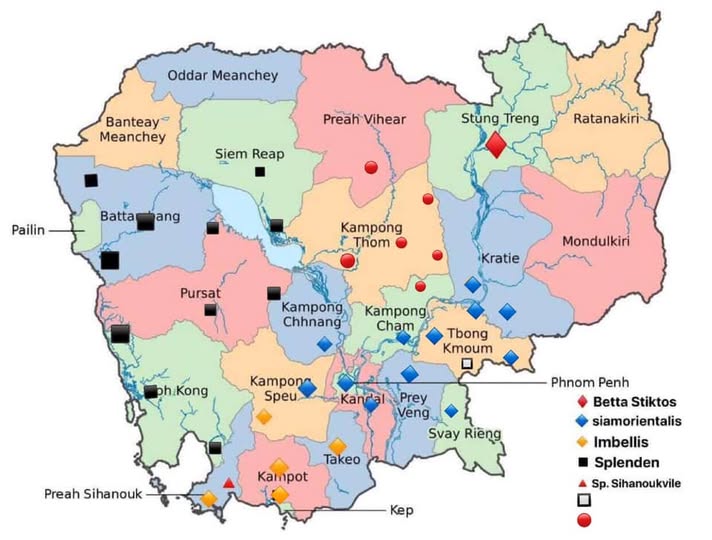

Betta stiktos Natural Habitat in the Wild

Alongside morphological characteristics, the geographic distribution and habitat type help distinguish Betta stiktos from its closely related congeners. Betta stiktos is endemic to the soft, acidic swamp waters around Steung Trung, Mekong drainage, Cambodia, whereas B. smaragdina is found in freshwater streams and paddies in North-east Thailand and Laos. B. mahachaiensis is known from brackish palm (Nypa fruticans) swamps in central Thailand, and B. splendens is known from freshwater rice fields and swamps in Thailand and Cambodia.

Collection sites of Betta species in Cambodia. Photo: Cambodia Wild Betta Conservation ©

Betta stiktos habitat near Krong Stung Treng, Cambodia. Photo: Kengo Togyoan ©

Betta stiktos habitat near Krong Stung Treng, Cambodia. Photo: Kengo Togyoan ©

Oleang Krous Betta habitat from above. Footage: Cambodia Wild Betta Conservation ©

Two Sister Jewels: Comparing Betta stiktos and Betta smaragdina

Although related within the splendens complex, B. stiktos and B. smaragdina reflect distinct evolutionary histories, shaped by the corners of the water they inhabit. Betta stiktos has a compact, robust body with a short, rounded snout, perfectly adapted to the slow, dark, and acidic waters of ponds and tributaries of the Tonle Srepok, where riparian forests filter the light and offer refuge with every movement. B. smaragdina, in contrast, is more slender, with an elongated snout and long fins that seem to flow with the current, and it lives in calm but more open bodies of water in northeastern Thailand, northeastern Laos, and parts of Cambodia. Its rice fields, ditches, and streams shaded by emergent vegetation create a tapestry of varied refuges and substrates, where mud, leaf litter, and sand sustain a vibrant aquatic life. The color of each species speaks of its world: B. stiktos exhibits dark tones, from deep brown to black, with metallic turquoise and lime green reflections that flash discreetly among the shadows; B. smaragdina, for its part, shines with an intense emerald green, adorned with iridescent bars that capture the sunlight filtered through leaves and reeds. Temperament also reflects their environment: B. stiktos is calm and reserved, adapted to the serenity of shaded waters, while B. smaragdina is more active and territorial, defending its space in slow but open currents. Still, both share the essence of the genus: males are bubble-nest builders and attentive caregivers to their offspring, an invisible bond that unites these sister species in the dance of evolution.

Betta stiktos. Photo: Minh Trí Kiệt ©

Betta smaragdina. Photo: Minh Trí Kiệt ©

Trey Ambok: Tradition and Conservation in Cambodia

For years, fishermen caught it incidentally, without recognizing its ecological or economic value. Today, thanks to educational projects and conservation programs, this species is beginning to be valued as part of the natural heritage and as a resource for responsible breeding and ecotourism.

Conservation of Aquatic Habitats and Species

The survival of B. stiktos is closely linked to the health of the riparian forests and wetlands of Steung Treng. Organizations such as the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) Cambodia, active in the region since 1999, work to protect these ecosystems against deforestation and environmental degradation. The preservation of the forests that border the Tonle Srepok maintains shade, regulates water temperature, and ensures its quality, fundamental conditions for B. stiktos and for other endemic aquatic species, such as fish, crustaceans, and amphibians. This approach shows that protecting an entire habitat not only benefits one species but also strengthens the river’s biodiversity and the resilience of ecosystems against human pressure and climate change.

Challenges and Trade

In 2012, the IUCN classified B. stiktos as Data Deficient (DD), reflecting the scarcity of information about its populations. Although there are no legal restrictions on its capture, its rarity and difficulty of access increase fishing pressure. International trade, especially to Thailand, has led to confusion with B. smaragdina and the proliferation of hybrids, complicating the identification of pure lineages. Ongoing taxonomic research is essential to fully understand the relationship between these species and to protect their genetic purity in the wild.

Betta smaragdina HYBRID. Photo: Minh Trí Kiệt ©

Conclusion

Betta stiktos is not just a fish with metallic reflections but a living symbol of the forests and rivers that still survive in Steung Treng. Its existence depends on the protection of wetlands and riparian forests, ecosystems that sustain not only this unique betta but also numerous aquatic species and the human communities that depend on the Tonle Srepok. Conservation efforts, such as those promoted by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) Cambodia, show that science, education, and local cooperation can transform the perception of these environments and protect them from human pressure. Preserving B. stiktos means keeping a fragile and complex ecosystem intact, reminding us that even in the darkest and most remote waters, natural treasures exist that deserve respect and care.

References

-Cambodian Wild Betta Conservation Project (Facebook group).

-Tan, H.H., & Ng, P.K.L. (2005). A review of the Betta smaragdina species group (Teleostei: Osphronemidae) with description of a new species from Cambodia. The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, 53(1), 75–84.

-Roberts, T. R. (1994). Collections of fishes from the Mekong River basin in northeastern Cambodia and central Laos, with description of two new species. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences, 48(9), 123–146.

-Interviews and Field Notes from Local Fisher Communities in Steung Treng.

-Kornfield, I., & Smith, P. F. (2000). Asian bettas: biodiversity and conservation challenges. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 57(2), 135–141.

-International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (2012). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Betta stiktos.

-Texts in Khmer (Cambodian) about Betta stiktos and traditional fishing.

-Photographs courtesy of Kengo Togyoan, Minh Trí Kiệt, and Gabor Horvath – All rights reserved ©